Wild soybean field tests document mineral content

- Domesticated soybean (G. max) has limited genetic diversity, putting it at risk for disease, pests, and changing climate conditions.

- Wild soybean (G. soja) are easily crossed with G. max and may bring positive phenotypic traits and increased nutrient content through selective breeding.

- New Crop Science research shows field test results for 81 accessions of wild soybean.

Like Michael Jordan at a high school basketball tryout or a freshly baked cookie before you dunk it in milk, some things have a lot of potential you might easily overlook. Wild soybeans are one of those things.

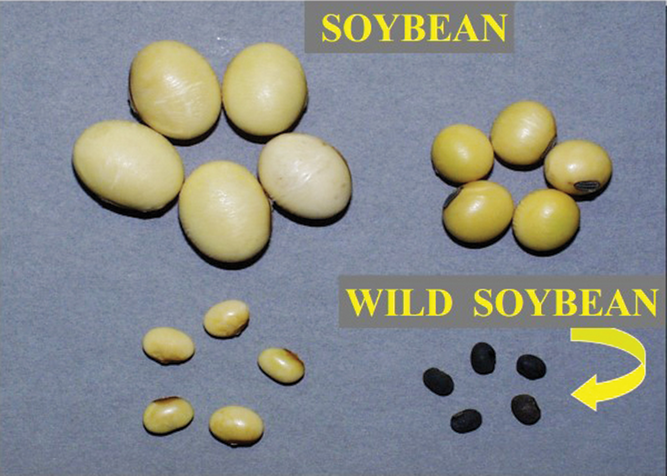

On the surface, wild soybeans [Glycine soja (L.) Merr.] do not look promising. They are prone to vine-type architecture, lower oil content, and small, brittle seeds compared with their domesticated counterparts. What you cannot see is their genetic diversity.

When bred with domesticated soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], hybrid crosses may have increased pest and disease resistance, better drought and low-temperature tolerance, and improved seed composition.

Adding Diversity for Improved Resilience

Domesticated soybeans are not genetically diverse—a bottleneck in their evolutionary history at the point of their import from Asia has made many lines of G. max susceptible to disease or changing climate. Domesticated lines are easily crossed with their wild counterparts.

“If a crop is not genetically diverse, it can be very vulnerable to a new disease. It can be vulnerable to drought,” Taliercio says. “If we bring in new genetic resources, hopefully we can improve resilience and have new resources available when breeders need to bring in new resistances and new resiliencies to environmental stress.”

Bringing in the positive effects of wild soybean's genetic diversity is not an easy task. “We're talking about breeding with wild soybean, and that takes, at minimum, two cycles of breeding. At best, a wild soybean is going to be a grandparent of an important line that's going to address a problem,” Taliercio says. Testing those lines to understand which have the best performance in the field, and, importantly, the highest yield and nutrient content, will help researchers make educated decisions about accessions to cross with the best of the domesticated lines.

Taliercio and his team put G. soja to the test using a “core collection” of 81 genetically diverse wild accessions to assess mineral content heritability. This “core collection” represents most of the diversity present in wild soybeans.

Over three years, the researchers planted wild lines from the core collection in fields in North Carolina and Missouri in a randomized complete block design. The researchers measured 19 different elements in the harvested soybeans using ion-coupled mass-spectrometry.

“By growing this subset in multiple environments, we were able to identify the inheritance of specific ions,” Taliercio says. “This was a great opportunity to really marry genomics and field work.” Taliercio expressed the need for collaboration between laboratory researchers— traditionally molecular biologists—and those with field experience.

Mineral Rich

Researchers found that wild soybeans were just as mineral rich as domesticated cultivars, with G. soja logging higher mineral content for seven different elements. Sodium content was the least heritable, with the greatest variation depending on environment and year. Sulfur content, on the other hand, changed the most depending on the accession. High sulfur content is positively correlated with protein content and economic value of soybeans, potentially giving farmers greater returns for the same yield.

More than 87,594,000 acres of soybeans were harvested in 2018 in the United States alone, with more than 70% of that harvest used as livestock feed, according to the USDA. By breeding to increase sulfur content in soybeans, researchers could help farmers decrease their need to add sulfur-containing amino acids to animal feed. That is, the crosses developed from wild soybeans may help breeders grow nutrient-rich crops that more efficiently take up and utilize soil minerals while at the same time, increasing their genetic diversity and disease resistance.

Like a coach with an eye for fundamentals or a cookie connoisseur with a handy glass of milk, Taliercio and his team spotted potential and fostered it. They identified favorable genetic diversity and catalogued genes to help increase soybean mineral content, yield, and abiotic stress tolerance before environmental changes negatively affect domesticated crops.

DIG DEEPER

Check out the original article, “The Ionome of a Genetically Diverse Set of Wild Soybean Accessions,” in Crop Science at https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2019.02.0079

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.