Ten years after Deepwater Horizon: Oil spill's impact on Louisiana's salt marshes

- 20 Apr. 2020 marks the 10-year anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

- Crude oil, spilled over 87 days, impacted 687 miles of Gulf coast wetlands.

- Research on the long-term impacts of the spill on the Louisiana salt marshes indicates complex relationships between soil, meiofauna, and plant health when affected by oiling and pollutants.

In the balmy late evening of 20 Apr. 2010, a $560 million oil rig exploded 40 miles off the Louisiana coast, releasing a fireball into the ocean air and killing 11 crew members.

“It became clear in the next few days that there was leakage, but no one, at first, realized the extent of it or certainly that it would last three months,” recalls John Fleeger, a professor emeritus at Louisiana State University (LSU) specializing in the evolution and ecotoxicology of benthic invertebrates.

Reports from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) cite failure of a cement plug placed in the well's wall tubing as the initial cause of the BP-owned Deepwater Horizon rig explosion and ensuing spill (https://bit.ly/2vi3F5Z). Unchecked by a blowout preventer, the pressurized oil from the 2.5-mile-deep well spilled into the Gulf, creating underwater plumes of natural gas and crude oil. The most buoyant oil accumulated in a slick on the ocean's surface.

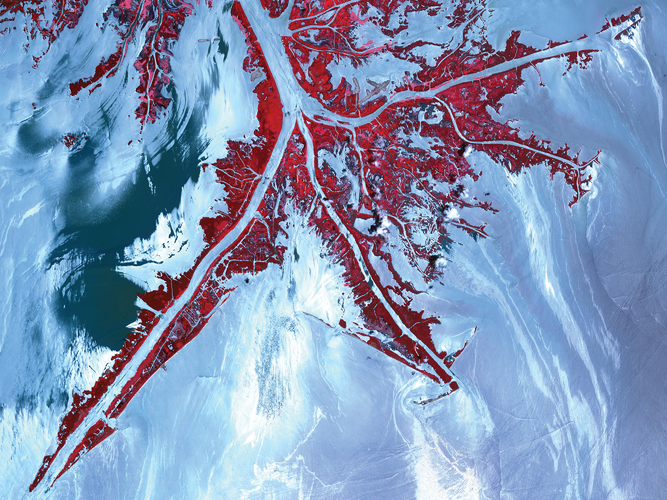

“It was so big, we could track it by satellite,” says John White, ASA and SSSA member and Associate Dean of Research and John and Catherine Day Professor in the Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences at LSU. “You could see the oil get caught up in this loop current. It was a matter of what the winds were going to do and how the currents were going to move, so we could see where this oil would end up on shore.”

White, like his colleagues at LSU, was in a unique position. Though no one wants to see an environmental disaster of this magnitude, LSU professors immediately leapt at the challenge to understand what was going to happen to the delicate coastal salt marshes in the path of the spill.

As the oil slick continued to grow and make its way through the Gulf, BP pledged up to $500 million over 10 years to fund research on its environmental impact, creating the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (https://bit.ly/39ZP7GI).

Now, at the 10-year anniversary of the wellhead blowout, the accumulated research on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill gives us a glimpse into its effects on the coastline and the organisms that live there. From the ground up, we're going to examine how the spill impacted the salt marsh soil, microbes, and plants that have been recovering for the past decade.

Crude Oil

Crude oil is the reduced form of carbon. Energy rich and hydrogen laden, it contains compounds as diverse as the petroleum that powers cars to the highly aromatic chemicals that make up paint thinners to the heavy, gunky hydrocarbons that make up asphalt.

Transformed over vast geological time and under immense amounts of pressure, researchers consider “fresh” crude oil to be its most toxic form. Fresh oil has not been separated into its component parts for consumer use or weathered by contact with the environment after extraction. In both weathering and commercial fields, this is referred to as oil “fractionation.”

Crude oil has a heavy and light fraction. The heavy fraction tends to clump and can sometimes sink, accumulating in the sediments on the ocean floor (Pietroski et al., 2015). If a hydrocarbon contains 16 carbon atoms or less, it's considered part of the light fraction. This fraction tends to be more hydrophobic, more aromatic, and thus more toxic as it coats the plants, animals, and soils it contacts.

As soon as fresh oil left the wellhead and contacted saltwater, the weathering process began. Oil-eating microbes and bacteria in the water column began degrading available hydrocarbons. Lighter fractions evaporated. Sunlight oxidized some carbon chains, and the emulsifying action of waves and wind began physically altering the oil (Overton et al., 2016).

In some places, floating weathered oil formed long, viscous strands. Tar balls of heavily degraded oil washed up on shore in places like Gulf Shores, AL and Pensacola, FL.

“The oil that came ashore is not the same oil that came out of the well, ” White says. “As it weathers, it gets heavier and heavier. There were points where it came into the wetlands and formed almost a pavement, it was so thick.”

Oil Fingerprinting

As the spill carried on for the better part of three months, emergency responders and scientists alike were unsure where the oil would end up. Like a well-mixed oil and vinegar salad dressing that's left on the counter a little too long, the crude oil spread throughout the water column and accumulated at the sea surface. It then traveled on currents and waves throughout the Gulf and was washed ashore.

This is where Ed Overton's work comes in. A professor emeritus in the Department of Environmental Sciences at LSU and contracted employee of NOAA's Emergency Response Division, Overton specializes in a method of retroactive oil tracking using a particular “fingerprint.”

“The various hundreds of thousands of chemicals that make up oil are virtually the same whether it's from South Louisiana or Texas or Alaska or Saudi Arabia or Venezuela,” Overton says, “but the quantities vary.”

Using the heaviest, most stable chemical components—biomarkers like hopanes and steranes—Overton's lab compares the chemical ratios of a known sample from a certain spill with an unknown sample from the environment. The team isolates oil from a sample of soil or water and then runs the isolate through a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (GC-MS). The outcome is a fingerprint that, like a crime scene, may or may not match up with the known sample's ratios (Overton et al., 2016).

In doing so, they can see how far the oil from a certain spill has traveled, even years after the spill occurred. This method was used in many of the studies conducted after Deepwater Horizon to ensure that researchers were, indeed, looking at oil from the BP wellhead.

Dispersant

Understanding the reach of an oil spill is important, but crude oil was not the only compound released into the environment during the spill.

In an effort to keep the oil slick from reaching land, the USEPA authorized the use of a dispersant called Corexit 9500A. In theory, a dispersant breaks up spilled crude oil just as soap cleans grease out of a frying pan.

Like soap, a dispersant molecule has a hydrophilic, polar head with a hydrophobic, non-polar tail. The hydrophobic tail is attracted to the oil while the hydrophilic head is repulsed. Dispersant molecules engulf an oil droplet, creating a micelle. The micelle is essentially a sphere formed with the polar, water-soluble part of the dispersant on its surface while the non-polar component is attracted to the oil, sheltering it at its core. The polar exterior of the micelle allows it to dissolve in water, allowing the non-polar oil to mix into the water column rather than floating on top.

The theory holds that oil droplets, now readily able to mix into the water, will disperse throughout the water column and be consumed by oil-eating bacteria and microbes. The pollutant is removed from the water's surface, breaking up the slick.

Breaking up the oil slick prevents masses of weathered oil from making landfall. When applied in deep water, the dispersant functions to spread the pollutant through the water column, decreasing its concentration.

The technique is not without controversy.

“What do we want to trash? Do we want to trash the shoreline, or do we want to trash the deep blue water? That's our choice at that point, it seems,” says John A. Nyman, a professor of wetland wildlife ecology in the School of Renewable Natural Resources at LSU. “I think they certainly did their best to use a dispersant only in deep water, but that oil was in deep water, and it still came ashore. So it's possible, I assume, that dispersed oils came ashore also.”

In total, according to a report by NOAA, 1.84 million gallons of dispersant were applied. Though using dispersants on the water surface is a common technique for major oil spills, a non-traditional approach was taken during Deepwater Horizon. Instead of surface application, 0.77 million gallons of dispersant were injected into the stream of pressurized oil coming out of the wellhead on the ocean floor (https://bit.ly/2vf3msF).

Little is known about the fate of the injected dispersant. Though the goal was to prevent the oil from reaching the surface by forming micelles directly in the water column, there is a possibility that the dispersed oil became another form of pollution. Responders typically only use dispersant when a spill is far offshore and in deep water.

The Salt Marsh and the Soil

With an understanding of oil composition, oil fingerprinting use, and the application of dispersant, one can see that the sheer volume of pollutants released into the Gulf of Mexico had the potential for massive environmental impact.

Over the course of 87 days, 168 million gallons of Louisiana sweet crude oil travelled from the wellhead into the water column and to the ocean's surface. More than 687 miles of coastal wetland shoreline were polluted, including 350 miles of Louisiana's salt marshes. Areas in Barataria Bay were among the most heavily oiled, according to NOAA.

Barataria Bay lies just west of the Mississippi River. The salt marshes surrounding the bay act as a buffer, slowing surges from tropical storms. They serve as nurseries for reproducing birds, fish, and invertebrates. They promote denitrification through microbial activity in the soil.

Denitrification occurs in the top 5 cm of wetland soil, reducing the amount of nitrogen in the water. This valuable ecosystem service decreases the negative effects of eutrophication, algal blooms, and low oxygen content in the water (Bargu et al., 2011).

From the ground up, soil serves as the medium for growth in the salt marsh. Soil health is directly related to microbial activity and supports the plants and meiofauna that, in turn, support larger animals.

Many of the immediate negative impacts associated with oil spills have to do with their physical properties: they physically suffocate plants and prevent proper oxygenation of the soil, increasing stress on plant roots. Its high-energy content encourages digestion and oxidation by microorganisms, often depleting water oxygen and further stressing plants and microorganisms (Overton et al., 2016).

Microbes and Meiofauna

Nothing can accurately be said about soil health without considering the tiny organisms within it.

“Think about the soil in the wetland like the hard drive of a computer, and the microbes are the operating system,” White says. “The soil doesn't do anything without the microbes—the microbes are what make things happen. They provide nutrients for plants, remove and break down contaminants.”

As oil came ashore and began settling on the marshes and the coastline, researchers attempted to understand how varying levels of toxic substances from the spill were affecting soil microbes.

A study by John White and his colleagues Jason Pietroski and Ronald DeLaune, all of LSU, indicated that dispersant, even at small concentrations, has the potential to negatively affect wetland soils (Pietroski, White, & DeLaune, 2015).

Researchers applied dispersants to soil samples from Barataria Bay that ranged from unoiled to moderately and heavily oiled and then applied varying levels of Corexit EC9500A. Their findings indicated a decrease in nitrogen mineralization and denitrification in exposed soils.

White hypothesizes that the dispersant was breaking the cell membranes of the microbes that digest oil in the soil. “When you put in a surfactant like that, we found that when it mixed into the soil, it really lowered the microbial activity overall,” White says. “We just found that the surfactant was harming the microbes that were doing important processes like denitrification, cleaning up the water.”

Decreased N mineralization means that the nitrogen necessary to stimulate plant growth may not be present in exposed marshes, adversely affecting their recovery. Decreased rates of denitrification are an indicator of poor water quality, in which excess nitrogen could trigger unhealthy levels of algal blooms that decrease water oxygen levels.

In another study focused on soil health and its ecosystem services, White and his team looked at a phenomenon called “re-oiling.” As weathered oil coats the landscape in a salt marsh, its sticky, dense, hydrophobic nature prevents it from just being washed away with the tides. The tides, salt marsh flooding, and plant matter that fall on top of the oiled areas do, eventually, form a layer of soil.

As waves hit and the stressed salt marsh erodes, the buried layer of oil is exposed again, re-oiling areas of the marsh that may no longer appear to be contaminated. Re-oiling effectively extends the lifespan of the spill, as recovering marshes receive another dose of weathered oil.

In a study involving samples including buried oil, White and his colleagues found that re-distributing oil throughout the soil results in decreased denitrification rates, but in soil where the oil remained buried, denitrification rates in the upper soil layers were unaffected (Levine, White, & DeLaune, 2017).

These findings indicate the resilience and importance of the soil. Even with a buried layer of oil, the positive services provided by the uppermost, biologically active layer persist.

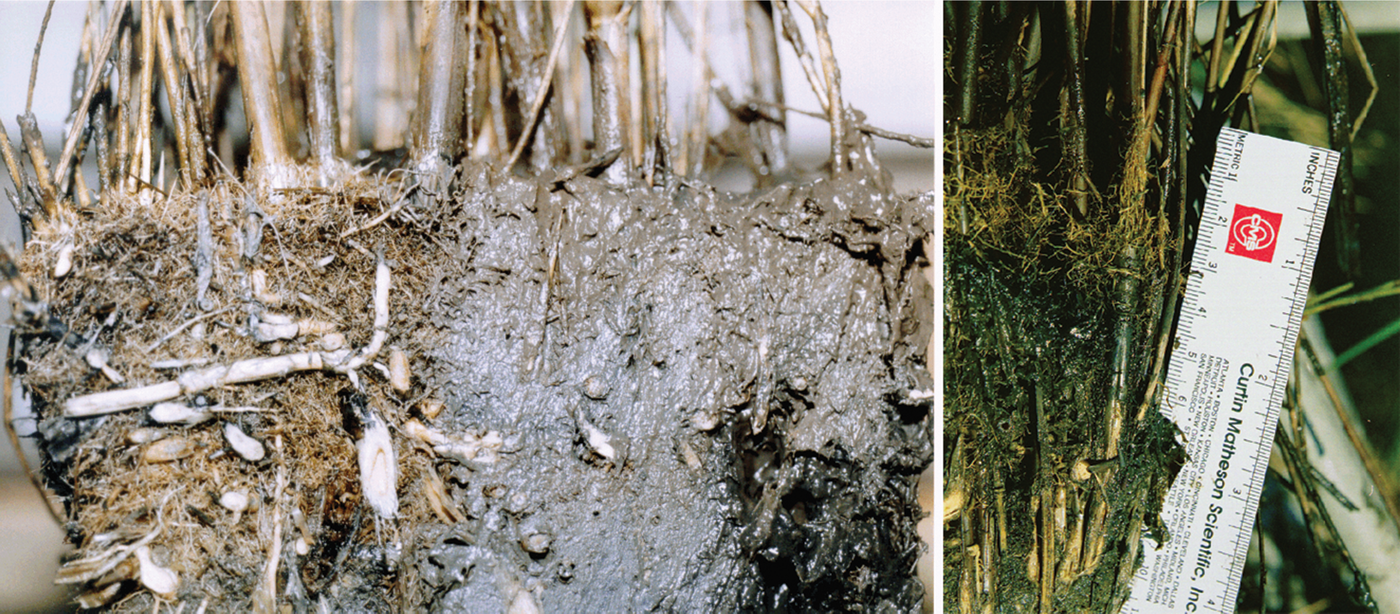

Another researcher at LSU, John Fleeger, undertook a six-year study to look at the recovery of infauna, which are the tiny benthic animals that serve as indicator species for soil health after a disturbance.

Meiofauna—microscopic but multicellular animals that live within the soil as infauna—are particularly helpful for gauging soil recovery. Meiofauna also serve as important food sources for post-larval fish and shrimp, and their well-being positively impacts animals farther up the food chain.

In a healthy ecosystem, a diverse array of meiofaunal and microbial species live in the soil, ensuring that important ecosystem functions like denitrification take place. However, when an environment is heavily disrupted, “opportunistic” infauna often dominate the population. Like weeds, when opportunistic infauna have room to grow, they grow in abundance.

“They tend to thrive in conditions that are disturbed,” Fleeger says. “As conditions improve, other species that have greater sensitivity to the oil or disturbance start to come back, and those early colonies of opportunistic species tend not to do as well.”

Monitoring the species diversity and populations of infauna in a soil sample, then, allows researchers to understand how the recovery process is progressing in a disturbed area.

Fleeger and his team, over the course of their six-year study, found a drastic initial reduction in meiofauna populations at heavily oiled sites while at moderately oiled sites, population numbers bounced back within about 18 months (Fleeger et al., 2018).

In moderately oiled sites, populations of meiofauna reached levels similar to unoiled sites in about four years. In heavily oiled samples, recovery was still not complete after six years of sampling, but populations had slowly increased since the first collection date.

Benthic community recovery was closely linked to the health of the predominant plant in Louisiana salt marshes: Spartina.

“Plants are the biggest factor that affected microbial activity positively,” Fleeger says. “As plants are recovering, the animals are recovering.”

In the long run, healthy plants improve soil quality. The recovery of some meiofauna species was linked to positive increases in soil characteristics like increased biomass of root and rhizomes and higher soil bulk density. Together, these factors stress the importance of revegetation and plant health in heavily oiled marshes as being key to ecosystem recovery and long-term health.

Salt Marsh Plants

The positive relationship between salt marsh plants and the benthic community has led more than one researcher to postulate that stimulating plant recovery might be the most efficient way to help the overall ecosystem.

In Barataria Bay, two species predominate: Spartina alterniflora and Juncus romerianus. Commonly known as cordgrass, S. alterniflora is found in wetlands as a native species on every coast of the United States, according to the USDA (https://bit.ly/2T33kx2). Also known as needlegrass rush, J. romerianus is native to the southern coastal wetlands.

Both species serve as important belowground habitats for the infauna that are vital to the health of the marsh soil. These plants also prevent the erosion of the wetlands and the coastline.

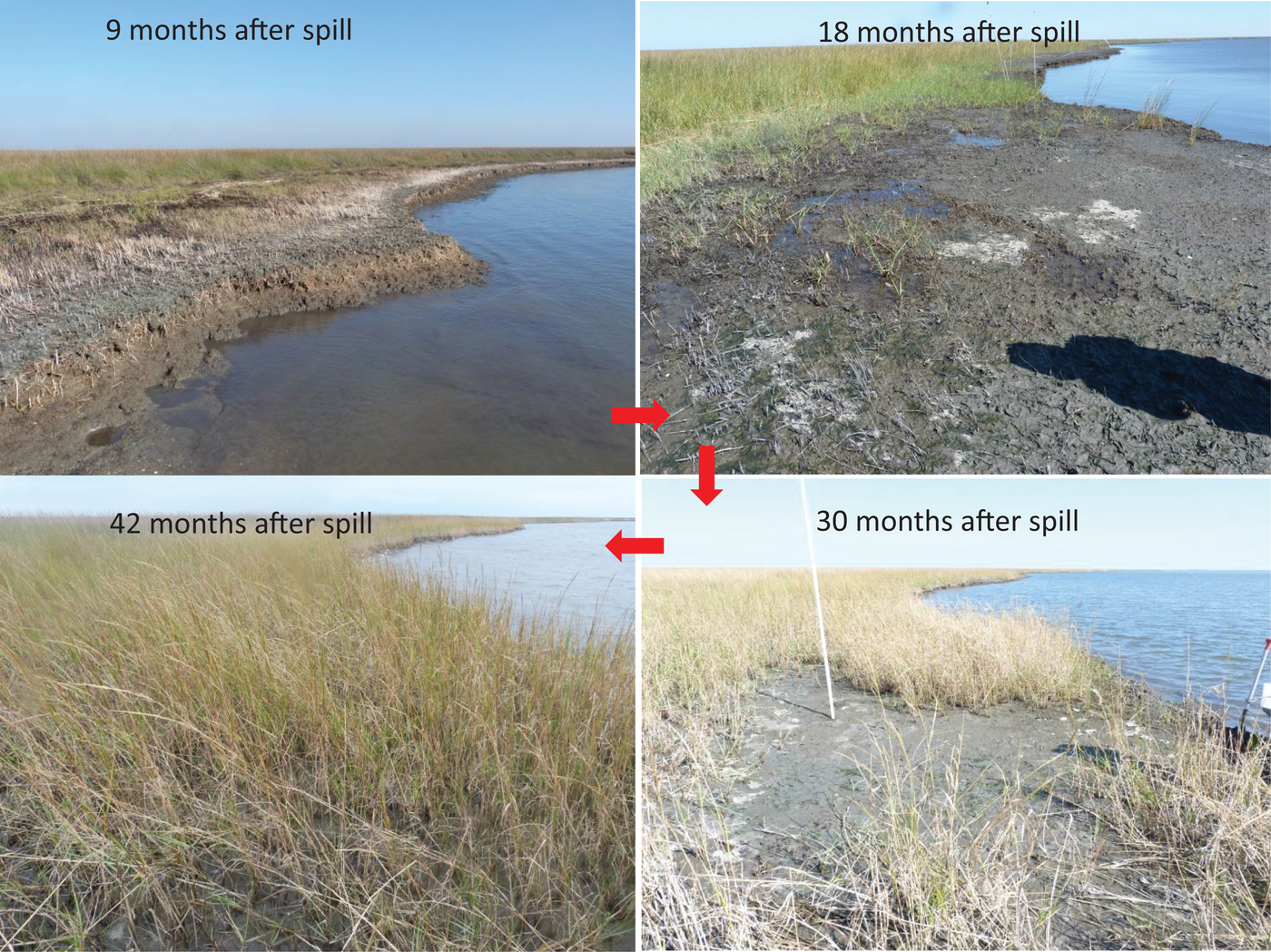

When oil finally contacted the coastline in 2010, the most heavily oiled areas showed high initial rates of plant mortality and then began recovering in a process that resembles recovery of marshes undergoing habitat restoration (Fleeger et al., 2018).

Building on the findings of his previous research, Fleeger was a part of another team that utilized both S. alterniflora plantings and supplemental fertilizer as a means of encouraging salt marsh recovery (Johnson et al., 2018).

The team waited until the initial re-colonization of the benthic community after Deepwater Horizon, and then, in the spring of 2014, transplanted S. alterniflora to unvegetated plots that were heavily oiled in the spill.

By comparing the meiofauna populations over time in plots that received transplants alone, fertilizer alone, a combination of transplants and fertilizer, or nothing at all, the team was able to see the effects of each treatment. Within two months, sites that received transplants showed increased populations of a polychaetae Capitella capitata compared with sites that did not receive transplants. Capitella capitata is an “early colonizer”—an opportunistic species that is an indicator of the very first step in recovery of an affected salt marsh.

Fertilizer provided an initial boost in benthic microalgal communities but did not increase the number of invertebrates. Though fertilizer has been postulated to be a good means of encouraging plant growth after such sharp population decline, it encourages plants to decrease growth of roots and rhizomes and allocate more resources into growing aboveground biomass.

Though, on the surface, this may seem beneficial, decreased belowground growth slows the recovery of the soil environment. It could be that plant transplants—encouraging a rebuilding of the natural habitat lost through oiling—is more effective for long-term marsh health.

Salt marsh vegetation, particularly S. alterniflora, is notable in its method of combating flooding stress and the horizontal erosion caused by waves. Wetland plants build up vertically. As the plant shoot grows, the roots continue to “climb” up the stem, creating more avenues to get oxygen and accumulating sediment in the open spaces between the roots and rhizomes.

This process, dubbed “vertical accretion,” keeps the plants from drowning during floods and gives the sediment a sturdy place to land. Understanding the strong relationship that a healthy plant base has with the overall marsh makes it clear that taking care of the salt marsh plants may be the best way to care for the wetland.

“When the marshes are keeping up with the rising water levels or the sinking ground,” says LSU's Nyman, “it's a self-reinforcing, stable feedback system.”

The Current State of the Marsh

Ten years after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill devastated the Louisiana salt marshes impacted by heavy oiling, there is still much to learn. Though tourism has returned, commercial fishing and nurseries are up and running, and much of the plant life has re-grown, it is still far from recovered.

The very nature of contaminating crude oil, perforce, dictates the way the ecosystem was impacted and how it will grow from now on. Overton emphasizes the need to understand the way oil differs from toxic compounds that have caused other environmental issues.

“Hydrocarbons have a lot of free energy,” Overton says. “I think a lot of people look at an oil spill and see what happened with the DDTs and the PCPs and the chlorocarbons. … We just have to understand the difference between an oil spill and a spill of conventional pollutants. Unfortunately, impacts are very quick with oil spills; it's an acute versus chronic type of situation.”

Like a car crash, the damage to the coastline ecosystem was immediate. Plants died, infauna populations tanked, and animals in the water column, heavy with dispersed oil, suffered. Because hydrocarbons are filled with stored energy in their atomic bonds, oil adversely impacts the environment as this energy is released. Unlike DDT, PCPs, or other pollutants, the negative effects of oil spills are not from long-term bioaccumulation, but from the energy that the oil releases into the ecosystem as it reacts. Just as passengers in a car crash may survive but feel the ill effects throughout their life, the marsh was hit hard right after the spill, and survived. But it may never be quite the same.

One defining factor is the level of stress placed on the salt marsh plants. Nyman notes that even momentary stress on a plant population can mean a downward spiral in the plant's ability to keep up with wetland flooding and horizontal erosion from wave action.

“We've got convincing data from numerous observations that oil is accelerating the shoreline erosion of these marshes,” Fleeger says.

Likewise, White mentions the difficulty of studying an ecosystem over long periods of time in which the shorelines are eroding at a rate of 1.5 m/year. “In some cases, our sites have disappeared,” White says. “Several of the islands we've worked on aren't there anymore—they've been completely eroded away.”

Even 10 years after the spill, researchers are still finding oil along the coastline. Though erosion rates consistently signal the loss of research sites and a decrease in the valuable ecosystem services provided by the marsh, re-sedimentation stands as a possibility for further recovery.

The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will take a section of the Mississippi River that has been isolated from the wetlands through human intervention (through levees to prevent unwanted flooding) and reconnect it.

According to Restore the Mississippi River Delta, a coalition of environmental organizations dedicated to rebuilding Louisiana's coastline, the sediment diversion will tentatively build 30,000 acres of wetland over 50 years (https://bit.ly/2TiTMNm).

Re-connecting the Mississippi River to the marshes will re-introduce a source of sediment that helps the wetland grow both vertically and laterally and combat the constant erosion from waves and flooding stresses. Construction is slated for completion in 2021.

With any luck, the sediment diversion and the recovery of the ecosystem over the past 10 years will mean that the plants, animals, wildlife, and ecosystem services of Barataria Bay will be present for many generations to come.

DIG DEEPER

Interested in this topic? Check out these related upcoming items:

- In April, SSSA will be dedicating three blogs on its Soils Matter Blog to the topic of soils and wetlands, how scientists helped determine and solve some issues related to the Deepwater Horizon spill and where the wetlands are in their recovery. Check them out at: https://soilsmatter.wordpress.com.

- Our podcast, Field, Lab, Earth, will be releasing two episodes relating to oil spill cleanup on land and sea. The episodes will cover progress made since the Deepwater Horizon spill (3 April) and techniques used in oil fields in North Dakota (17 April). Listen for free anytime by scanning the QR code below or by visiting https://apple.co/2SpCoGs on Apple devices or https://bit.ly/2Sqf7nM on Android. Subscribe to never miss an episode.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.