Enhancing farm profitability through nitrogen efficiency and yield stability

This article explores how understanding within-field yield variability can improve nitrogen use efficiency and farm profitability across the U.S. Midwest. By integrating long-term yield data, satellite imagery, and field-level nitrogen information, it identifies stable and unstable productivity zones to guide targeted nitrogen management. The findings highlight opportunities to reduce environmental impacts, lower input costs, and optimize crop performance through precision agriculture strategies.

Earn 1 CEU in Nutrient Management by reading this article and taking the quiz.

Nitrogen (N) is the most critical nutrient influencing corn yields in the U.S. Midwest where highly productive soils and favorable climates support nearly one-third of the world’s corn production. Yet, the response of corn yields to applied nitrogen is spatially and temporally heterogeneous, reflecting differences in soils, climate, management, and underlying biophysical processes.

Research consistently shows that corn yield response to nitrogen follows a nonlinear curve; more specifically, yield increases sharply at low to moderate application rates and then levels off as nitrogen becomes non-limiting. The agronomic optimum nitrogen rate (AONR) varies substantially across fields and even within fields, ranging from less than 100 lb N/ac on fertile, organic-matter-rich soils to more than 250 lb N/ac on sandy or degraded soils.

Long-term trials across the Midwest indicate that while average yields have steadily increased due to genetic gains and management, the shape of the N response curve has not changed dramatically despite increases in N rates (Baum et al., 2025), highlighting persistent variability in nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). While nitrogen inputs remain essential for sustaining high yields, the efficiency of use is limited by environmental losses and mismatches between supply and demand.

Several factors contribute to the spatial and temporal variability of the yield response to N fertilizer:

- Soil properties: Organic matter content, texture, drainage class, and mineralization potential strongly regulate nitrogen supply. Poorly drained soils often exhibit a greater yield response to applied nitrogen due to denitrification losses.

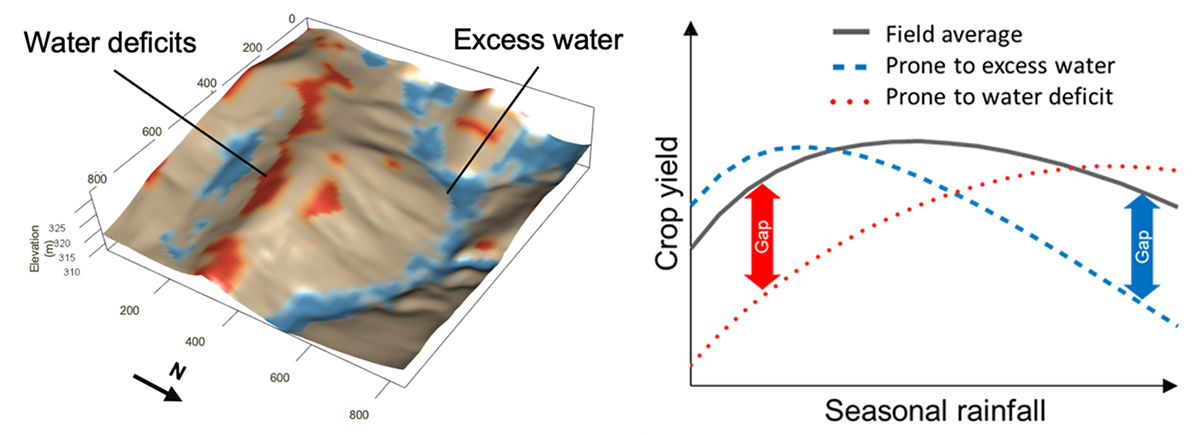

- Climate and weather: Rainfall amount and timing, intensity, and seasonal temperature patterns interact with nitrogen availability. Wet springs accelerate leaching and denitrification while drought conditions can reduce uptake efficiency.

- Management practices: The timing, placement, and form of nitrogen application significantly influence recovery efficiency. Split applications and sidedress strategies often improve NUE relative to pre-plant broadcast.

- Position in the landscape: Terrain attributes (slope, aspects, and profile curvature) strongly influence the interaction between soil and climate with alternating results depending on wet or dry years, soil texture, and topographic features.

- Cropping history: Previous crops, especially legumes, alter soil N supply and residual effects on corn N demand.

Concept of yield stability zones

Yield stability mapping represents a transformative step in precision agriculture and digital agronomy. While yield monitors on combines began generating detailed spatial data in the 1990s, most early uses were limited to single-year yield maps. These snapshots highlighted variability, but they lacked the temporal dimension necessary to distinguish persistent patterns from year-to-year noise caused by weather. Basso et al. (2019) were among the first to recognize that long-term analysis of yield data at scale could reveal stable zones of productivity within fields, thereby converting variability from a challenge into an opportunity for management.

Basso’s conceptual advance was to apply time-series analysis across multiple seasons of yield monitor data, thereby generating what we now have termed yield stability maps. These maps classify each portion of a field into zones such as:

- Stable–high yield zones—consistently productive across seasons, usually linked to deeper soil depth, higher organic matter, and greater water-holding capacity.

- Stable–low yield zones—consistently low productivity, often associated with shallow soils, poor drainage, low organic matter, eroded soils, compacted layers.

- Unstable zones—variable productivity from year to year, reflecting strong sensitivity to climate fluctuations such as drought or excess rainfall and their position in the landscape (hilltops vs. low-lying areas).

Basso connected stability zones to the biophysical drivers of yield, including soil texture, organic matter, rooting depth, topography, drainage, and microclimate, demonstrating that much of the variability observed in fields is systematic and predictable, rather than random, particularly for the stable zones (Basso et al., 2019). This insight carried powerful implications: if low-yield zones are consistently unresponsive to inputs like nitrogen, then uniform fertilizer application is not only wasteful, but environmentally harmful. Conversely, stable–high zones respond better to higher nitrogen rates and NUE so that they can justify intensified management (Basso & Antle, 2020; Basso, 2021).

Identifying yield stability patterns

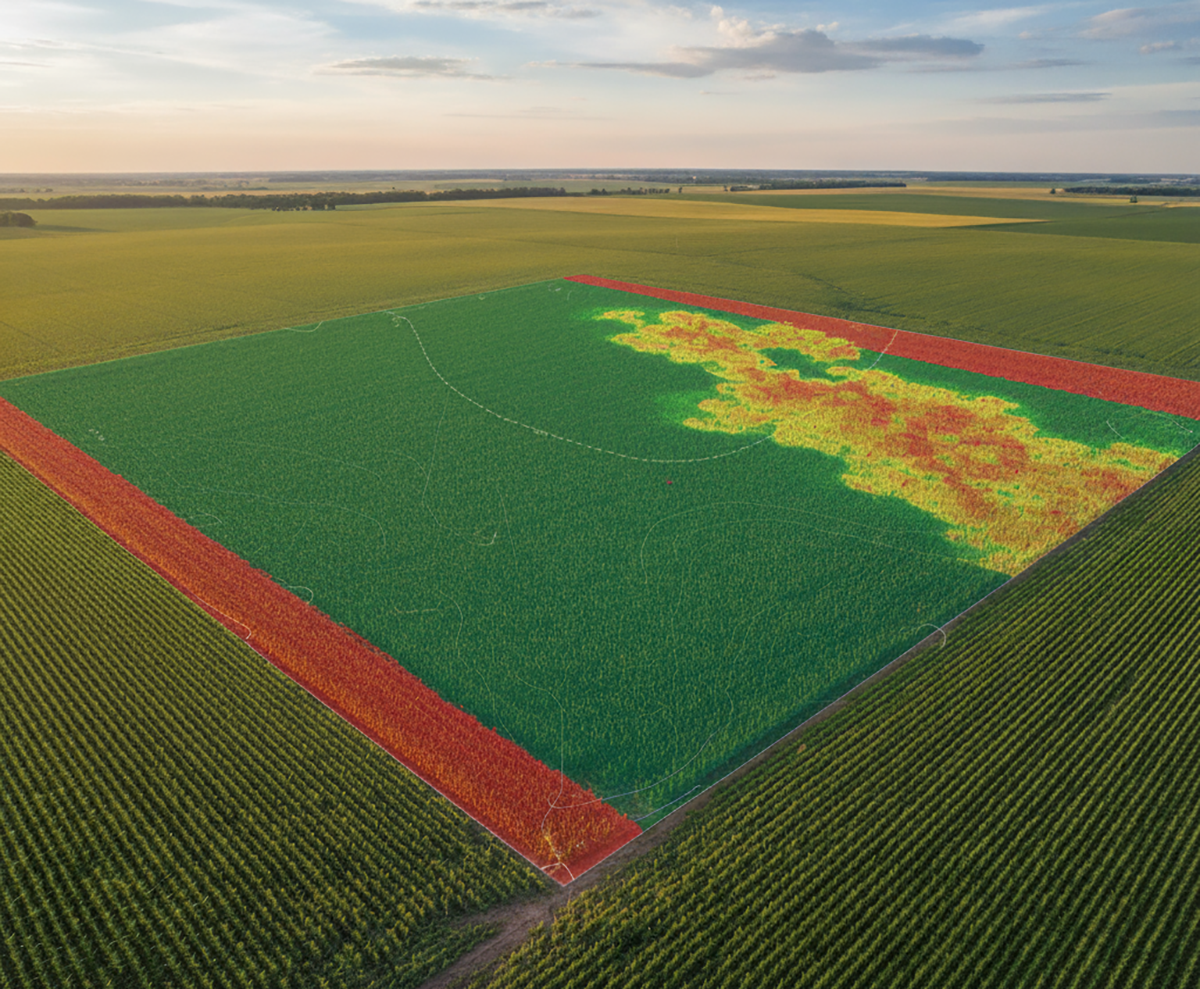

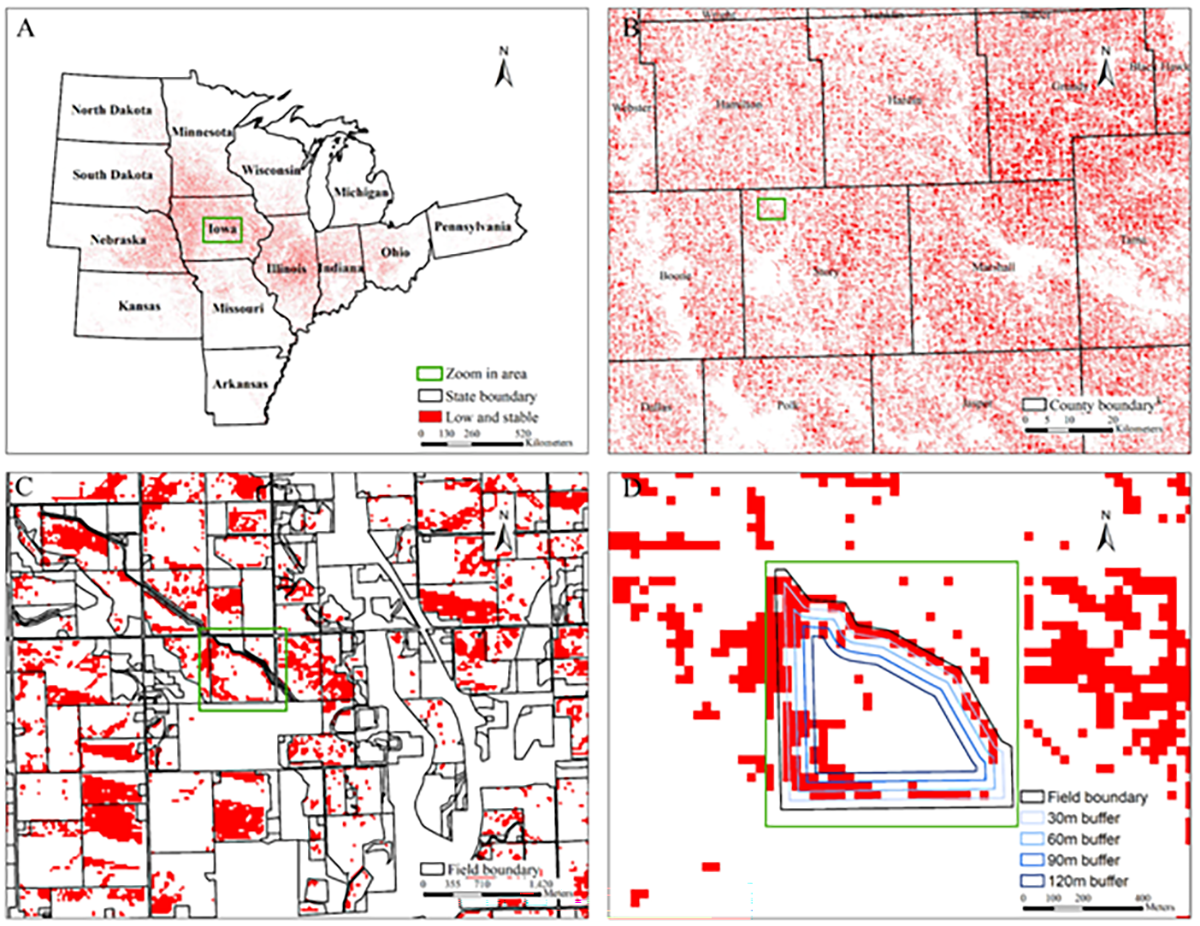

To generate yield stability maps and calculate nitrogen balances, multiple sources of spatial and agronomic data were integrated. The process begins with several foundational datasets. Cropland Data Layers (CDL) from the USDA were used to identify which fields were planted to corn or soybeans. High-resolution satellite imagery from Landsat-NASA (5, 7, and 8) and now from Sentinel 2 (ESA) provided normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) data at 30- and 10-m resolution for each growing season. These images, particularly those from late July when NDVI is highly correlated with yield, capture the spatial variability of crop growth across fields. The Common Land Unit (CLU) boundaries supplied by the USDA Farm Service Agency define the field polygons, ensuring that the analysis respects real-world field edges. In addition, county-level nitrogen fertilizer application rates from farmer surveys (Agricultural Resource Management Surveys, or ARMS) and university recommendations (maximum return to nitrogen, or MRTN) are incorporated.

The next step is to process the NDVI imagery to detect consistent patterns of productivity within fields. For each pixel, NDVI values are normalized relative to the field average, and temporal variation is assessed across multiple years. Pixels that remain consistently above the mean with little year-to-year variability are classified as stable–high yield zones. Those consistently below the mean are labeled stable–low yield zones while pixels that fluctuate substantially from year to year are marked as unstable zones. This classification results in yield stability maps that capture the spatial and temporal reliability of crop production within each field.

With stability zones in place, crop yield estimates are derived by scaling county-level USDA yields down to the subfield level using the proportional differences in NDVI. Grain nitrogen uptake is then calculated by multiplying yield by grain N concentration. Fertilizer inputs are assigned based on ARMS survey averages and MRTN recommendations, providing both conservative and upper-bound estimates of nitrogen application. From these inputs, a nitrogen mass balance is constructed for each stability zone. Nitrogen use efficiency is calculated as the ratio of grain N uptake to fertilizer N applied. Surplus nitrogen, defined as the difference between fertilizer applied and nitrogen removed in the harvested grain, is interpreted as nitrogen lost to the environment through leaching, volatilization, or denitrification.

Finally, these balances are aggregated across stability zones and states to estimate the magnitude of nitrogen losses, their economic cost in terms of wasted fertilizer, and their environmental footprint in terms of embedded energy and greenhouse gas emissions. Stable–high zones typically exhibit high efficiency and low surplus, stable–low zones show poor efficiency and high losses, and unstable zones fall in between.

Through this analytical process, 24 million acres of stable–low zones were identified across the U.S. Midwest (Figure 1). Across the Midwest, approximately a third of the acres could be classified as low, stable zones (Table 1).

| Zone | Acreage (mil. ac) | Percent area (%) |

| High & stable | 42.0 | 51 |

| Low & stable | 24.0 | 29 |

| Unstable | 16.8 | 20 |

Dynamics of these yield zones are directly related to soil water across the landscape. There is a strong relationship between soil water availability and nitrogen response (Hatfield, 2012), and limited response to nitrogen is exhibited across the Midwest soils with low organic matter (low water-holding capacity). Seasonal patterns of rainfall show that late-summer rainfall doesn’t meet crop water demand, and with the limited soil water-holding capacity, corn is subjected to water stress, which ultimately limits its ability to utilize nitrogen in the soil profile (Maestrini & Basso, 2018). A typical topographic representation of a field shows areas that are prone to water deficits and water excesses (Figure 2). Examining areas of the field prone to either water deficits or water excesses relative to the seasonal rainfall shows how these areas affect the yield across the field (Figure 2).

Implications of understanding yield zones for enhanced management

Meanwhile, unstable zones highlight regions where adaptive strategies, such as variable planting densities or in-season nitrogen adjustments, can buffer against climate variability. Across millions of acres in the U.S. Midwest, uniform management leads to significant inefficiencies: (i) Economic inefficiency: resources are wasted on zones that never achieve high yields, lowering profitability; (ii) Environmental inefficiency: over-application of nitrogen in low-stability zones increases nitrate leaching in water and nitrous oxide (N₂O) emissions into the atmosphere, contributing to Gulf hypoxia and a higher carbon intensity score (Basso et al., 2019; Martinez-Feria & Basso, 2020; Maestrini & Basso 2021). Yield stability maps offer a scientifically robust method for quantifying dynamic baselines in carbon markets and conservation programs.

In contrast, stable–medium and stable–high zones exhibit higher productivity and clearer yield gains with increased nitrogen, reflecting their greater responsiveness and efficiency in utilizing applied nutrients. Unstable areas, such as depressions, slopes, and hilltops, display variable yields with wide ranges, emphasizing their susceptibility to site-specific soil and climatic factors. Overall, the results reinforce that strategic nitrogen management guided by yield stability analysis can reduce unnecessary fertilizer use in unresponsive stable–low zones while maintaining or enhancing yields in more productive zones. Stable–low zones represent low-efficiency environments for fertilizer investment. Applying higher N rates in these areas does not enhance yields but instead increases the risk of unnecessary input costs and environmental losses. In contrast, zones with higher productivity and greater yield stability continue to warrant targeted N applications to support crop growth and maximize returns. These findings highlight the importance of spatially explicit N management strategies where resources can be strategically reallocated away from unresponsive zones and toward areas where fertilizer use generates clear agronomic and environmental benefits.

Farmers can increase profitability by saving money and N fertilizer. The data shown in Table 2 were obtained from published USDA data with the estimated actual N uptake in the stable–low zones. Nitrogen use efficiency in the stable–low zones of fields averages 60%, which leaves a large amount of nitrogen fertilizer subject to loss from these zones (Table 2).

State | Fertilizer N rate | N uptake in SL | Fertilizer loss in SL | NUE (%) | N saved with SL if N uptake applied (lb/ac) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

lb/ac | |||||

| IL | 163–170 | 96 | 46–54 | 57–59 | 67–74 |

| IN | 156–186 | 88 | 47–78 | 47–57 | 68–98 |

| IA | 141–154 | 103 | 18–31 | 66–73 | 38–52 |

| MI | 135–147 | 85 | 29–42 | 58–63 | 50–62 |

| MN | 143–158 | 103 | 22–37 | 65–72 | 40–55 |

| MO | 176–194 | 76 | 82–100 | 39–43 | 100–118 |

| ND | 128–141 | 74 | 37–50 | 53–58 | 54–67 |

| OH | 155–174 | 89 | 46–65 | 51–57 | 66–85 |

| SD | 123–136 | 79 | 26–38 | 59–64 | 44–56 |

| WI | 104–115 | 89 | 0 | 78–85 | 15–26 |

| Average | 143–158 | 88 | 36–50 | 57–63 | 54–70 |

Extending these analyses across multiple states where corn is grown shows that large reductions in nitrogen applied can be achieved. Adoption of yield stability analysis in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana alone would reduce annual N application by more than 1 billion pounds and reduce the potential losses from these fields in both water quality and greenhouse gas emissions. The N savings from a simple reduction in N rate to match historical corn yields in the stable–low zones show a savings of more than 2 billion pounds of N per year across all of the states if the low yield areas are to be converted to pollinators or grasses (Basso, 2021). A recent article on the New York Times featured Basso’s research on farmers’ field in Michigan, highlighting the N saving, profitability gains for farmers and for the environment.

Strategic decision making by producers

The combination of yield stability analysis and profitability mapping enables farmers to reallocate management across their fields strategically. Persistent stable–low zones represent an opportunity for two distinct pathways: reducing input use or converting land into conservation habitat. Each path offers quantifiable benefits in terms of agronomic, economic, and environmental aspects. A simple economic analysis of reducing the nitrogen rate in the stable–low zones reveals that producers can achieve a savings of $24–32/ac. Using a field size of 320 ac with 20% of the field in the stable–low zone and a potential reduction of 54 lb N/ac and a cost of N at $0.45–0.59 per lb N shows a savings in this field between $1555 to $2040. This is a considerable savings by a simple adjustment in N application rate.

Implications for production and the environment

Identification of areas of the field that have low nitrogen use efficiency with a consistent response over time allows a producer to make an informed decision on different management options. Yield stability maps are available for fields, and taking advantage of this information will increase profitability when rates are adjusted to the appropriate level to meet crop demand, reduce the environmental impact of excess nitrogen loss from fields, or offer the potential to remove these areas from crop production to capture other economic and environmental benefits.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate the support from USFRA (United States Farm and Ranchers in Action) to prepare this synthesis as part of the ongoing effort to evaluate pathways to reduce the carbon footprint through increased efficiency in American agriculture.

Basso, B., Shuai, G., Zhang, J., & Godwin, D. (2019). Yield stability analysis reveals sources of large-scale nitrogen loss from the US Midwest. Scientific Reports, 9, 5774. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42271-1

Basso, B. (2021). Precision conservation for a changing climate. Nature Food, 2(5), 322–323. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00283-z

Basso, B., & Antle, J. (2020). Digital agriculture to design sustainable agricultural systems. Nature Sustainability, 3(4), 254–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0510-0

Baum, M. E., Sawyer, J. E., Nafziger, E. D., & Lory, J. A. (2025). The optimum nitrogen fertilizer rate for maize in the US Midwest is increasing. Nature Communications, 16, 404. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55314-7

Hatfield, J. L. (2012). Spatial patterns of water and nitrogen response within corn production fields. In G. Aflakpui (Ed.), Agricultural Science (pp. 73–96). Intech Publishers.

Maestrini, B., & Basso, B. (2018). Drivers of within-field spatial and temporal variability of crop yield across the US Midwest. Scientific Reports,8, 14833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32779-3

Maestrini, B., & Basso, B. (2021). Subfield crop yields and temporal variability in thousands of US Midwest crop fields. Precision Agriculture, 22, 1749–1767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-021-09810-1

Martinez-Feria, R. A., & Basso, B. (2020). Unstable crop yields reveal opportunities for site-specific adaptations to climate variability. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 2885. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59494-2

New York Times. (2025, September 22). Satellites and drones are unlocking benefits ‘hidden in plain sight’ in Michigan. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/22/climate/michigan-precision-agriculture.html

Self-study CEU quiz

Earn 1 CEU in Nutrient Management by taking the quiz for the article. For your convenience, the quiz is printed below. The CEU can be purchased individually, or you can access as part of your Online Classroom Subscription.

- Nitrogen rates are consistent among years within the same field.

a. True.

b. False.

The primary reason nitrogen rates have increased over time is

a. improved genetics.

b. more favorable rainfall patterns.

c. better forms of nitrogen fertilizer.

d. All of the above.

Yield zones within a field are determined by

a. position on the landscape.

b. soil texture.

c. seasonal rainfall patterns.

d. cropping history.

e. None of the above.

f. All of the above.

Low-yielding stable zones account for what percentage of Midwest crop area?

a. 10%.

b. 20%.

c. 30%.

d. 40%.

e. None of the above.

Low-yielding stable zones are primarily determined by

a. seasonal rainfall patterns and amounts.

b. management history.

c. organic matter and soil texture.

d. position on the landscape.

e. All of the above.

6. Which management strategy provides the greatest immediate economic benefit in low-yielding stable zones?

a. Reducing nitrogen inputs to match crop uptake.

b. Planting higher populations.

c. Increasing pesticide applications.

d. Switching to longer-season hybrids.

What benefits would the yield stability map bring to a farmer?

a. Increased profit.

b. Reduced cost.

c. Increased nitrogen use efficiency.

d. Reduced environmental impact.

e. All of the above.What are the drivers of high and stable zones?

a. Lower disease pressure.

b. Greater plant available water.

c. Alkaline pH.

d. Areas where water accumulates.

e. All of the above.

Precision conservation and precision farming can be used on the same field.

a. True.

b. False.

10. Precision conservation leads to

a. lower cost.

b. environmental benefits.

c. increased biodiversity.

d. improved soil health.

e. All of the above.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.