Handling Conflict in Graduate School

Conflict can be defined as “an active disagreement between people with opposing opinions or principles” (Cambridge Dictionary). Conflict is a normal component of our lives even though most people don’t like to experience it. It is important to learn how to handle conflict, so that we can overcome those unpleasant instances and disagreements in a positive and constructive way.

As graduate students, you will probably encounter conflict if you haven’t already. Conflict, for example, could arise as a small disagreement with a labmate about who should have the priority on using a shared piece of equipment or a technician who is suddenly expecting you to help with data collection or processing on a day when you had planned to catch up with your course requirements. Conflict could also present itself as a more intimidating situation; for example, a disagreement with your adviser about expectations towards the completion of your degree. Additionally, a study published in 2007, reported that other sources of conflict can be “lack of openness, time, and feedback; unclear expectations; and poor English proficiency” (Adrian-Taylor et al., 2007).

In all these instances, it is important to know how to handle conflict, no matter how big or small the problem seems. Being able to handle conflict can improve our relationships, both personal and in the school/work setting. An unsolved conflict can create friction and, in the long run, affect our ability to collaborate with others and openly discuss and solve future issues. Additionally, conflict can be used as an opportunity to develop skills (soft skills) in managing people—and conflict—that can help you in the long term.

Hoping to provide a useful and simple roadmap, in this article we will talk about solving conflict within, strategies for handling conflict, and general tips to keep in mind when faced with conflict.

Solving Conflict Within

Prior to handling a conflict with others, it is important to handle the conflict within us. According to the psychologist Daniel Goleman (1995), author of the book Emotional Intelligence (EI), self-awareness is one of the five components of EI. It is associated with the ability to be aware of the emotions, moods, and impulses that we experience and why as well as the effects that our thoughts and actions can have. Putting in the time to examine our feelings, patterns of behavior, and interactions with others can make a difference between acting assertively to solve a conflict or escalating it.

When dealing with a situation that our body senses as threatening, physiologically our body goes into a “fight or flight” response. Therefore, it is normal to feel triggered when we find ourselves in a conflict situation. Fortunately, it is in our control to decide how we approach the situation. The story we tell ourselves matters because it has an impact on how we react.

Prior to addressing a conflict situation, it is key to take time to understand what the conflict is, the causes, how we feel about it and why, how the other people involved feel, and how we could work together for a mutually agreeable solution. Once we solve the conflict within, we are better prepared for attempting to solve the conflict with the people involved.

Getting better at controlling our own emotions and automatic reactions is not easy, and it is a consistent work in progress. By committing to improve our self-awareness, we will be better able to handle conflict, make assertive decisions, and set the example to others to do the same.

Strategies for Handling Conflict

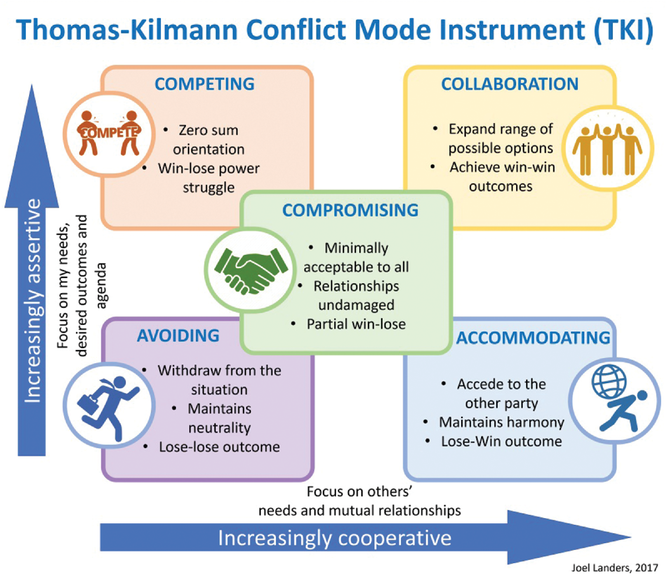

Being able to manage conflict is a valuable skill that will help you not only in academia, during graduate school, but also in your future workplace. According to Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann (Thomas, 2008), there are two basic dimensions of conflict behavior, assertiveness and cooperativeness. You can be more or less assertive, depending on the degree in which you try to satisfy your own concerns and ideas during a conflict. Cooperativeness is related to the degree in which you try to help the other individual's concern, how receptive you can be to the other individual’s idea, being also more or less cooperative. Thomas and Kilmann described five different strategies to manage conflict, in which one can be more or less assertive and more or less cooperative (Figure 1), all of them with benefits and costs:

The ability to manage conflicts appropriately is important for graduate students. Conflict can be an opportunity to develop or improve intrapersonal and communication skills.

Competing

This mode of conflict-handling is assertive and uncooperative—"this is “my way” mode. In this mode, you pursue your own concerns at the other person’s expense. Dr. Barbara Benoliel explains that this style is applied when you do not care about the relationship, but the outcome is important. The competing mode has an impactful effect, and in some situations, it can be quite destructive and break relationships. According to Kenneth W. Thomas, this strategy would be used in emergency situations when a quick and decisive decision needs to be made.

Avoiding

This mode of handling conflict is unassertive and uncooperative—this is “no way” mode. In this strategy of action, you try to sidestep from the conflict and do not care about either individual’s concern. This sounds negative for both individuals; however, there are certain situations in which “avoiding” is the best decision to take. Building and maintaining good relationships is a requirement in a workplace, so “avoiding” interaction with certain individuals may be the best strategy for maintaining relationships where the cost of that interaction can be too high.

Accommodating

This mode of handling conflict is unassertive and cooperative—this is “your way” mode. This is the opposite of “competing”; in this mode, you satisfy the other person’s concern at the expense of your own concerns. As a first impression, it may seem generous and kind; however, people can use this to take advantage of and exploit you. Also, if you are “accommodating” something that you care about, your interest is being sacrificed. A situation where you can use “accommodating” without further frustrations is when you don’t really care about the outcomes. Another good way to utilize the “accommodating” mode is when your sacrifice is small compared with the good you will be doing for the other person.

Collaborative

This mode of handling conflict is assertive and cooperative—this is “our way” mode. This is the opposite of “avoiding,” and you work together with others to find a solution that will completely satisfy everyone’s concern. This strategy builds trust and respect among people involved and usually results in high quality decisions. However, a lot more time and energy are needed to work in a conflict with this approach than any of the other strategies, as both parties have to be open to new ideas and challenges, resulting in a lot of time for discussion. According to Kenneth W. Thomas, this mode should be used only for very important issues.

Compromising

This mode of handling conflict is intermediate in assertiveness and cooperativeness— this is “halfway” mode. Using this strategy, you try to find an acceptable solution that will partially satisfy everyone involved in the conflict. This approach results in equal gains and losses for all parties. In general, compromising solutions is not the first or the best option; however, when the outcome is not crucial and you want to move on, it may be the most practical solution, knowing that the results may be unsatisfactory to all parts.

According to your personality, each one of us has a dominant mode to handle a conflict. For example, if you prioritize a good relationship with other people, you are more likely to act avoiding or accommodating when a conflict comes even if it means that you will be always sacrificing your concerns. To best manage a conflict when it arises, try asking these four questions:

- How much time do I need to solve it?

- How important is the relationship to me?

- How crucial is the outcome?

- How powerful are the other people involved?

The ability to manage conflicts appropriately is important for graduate students. Conflict can be an opportunity to develop or improve intrapersonal and communication skills.

Tips to Keep in Mind When Faced With Conflict

Of course, some situations might not be as clear-cut as the ones presented above, and finding the best strategy might not be so straightforward. For this reason, in this last section, we want to offer some general tips to keep in mind when faced with conflict.

Do Not Take the Situation Personally

In most cases, the people you are interacting with are not trying to attack or judge you as a person. Nonetheless, as mentioned above, in a conflictual situation, we could feel threatened or offended. Consequently, even though it might be challenging to control our instinctual reaction, it is important to focus on the actual cause of the conflict and keep a calm and professional reaction to the issue being discussed. More simply, remember to remain respectful in disagreement.

Make Sure to Understand the Other Person’s Perspective

As also reported by Adrian-Taylor et al. (2007), misunderstandings can be a common source of conflict. When finding yourself in disagreement with another person, make sure you are not misinterpreting their perspective, and stay open to their point of view.

Listen and Ask

Similarly to the previous tip, make sure you are listening to what the other person is trying to express. If you are not sure what the other person means or cannot grasp what informs their point of view, ask questions—a simple question might help clarify the situation and show that the source of disagreement is much easier to tackle than what you thought! Asking questions will also show the other person that you are open to listening to and understanding their needs, hopefully encouraging them to be cooperative as well.

Focus What Can Be Changed

Try to break down the issue into its core components and focus on the parts that can be changed. While you might not be able to solve every aspect of the conflict, you should usually be able to move to a more agreeable and comfortable situation. Additionally, understand there will be things you will have to accept for what they are.

Identify Win–Win Situations

Try not to be discouraged when conflict happens. In those moments, keep in mind that there could be a solution that could satisfy—at least in some way—both parties. Look for common ground, and use the points of agreement to find a win–win outcome.

Understand When to Bring a Neutral Third Party into the Conversation

On some, hopefully uncommon, occasions, you might not be able to solve the conflict alone. In those cases, the best solution might be to bring a third party to the conversation. This neutral person should be able to propose an alternative or at least help navigate the issue when you have reached an impasse.

References

Adrian-Taylor, S.R., Noels, K.A., & Tischler, K. (2007). Conflict between international graduate students and faculty supervisors: Toward effective conflict prevention and management strategies. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(1), 90–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306286313

Benoliel, B. (2017). What’s your conflict management style? https://bit.ly/3QvgizR

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam.

Landers, J. (2017). The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI). https://communicationinpublichealthweb.wordpress.com/mangement-styles-and-conflict/

Thomas, K.W. & Kilmann, R.H. (1974). Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02326-000

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.